- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The term 'equalisation' comes from the

pioneering days of the telephone, when it described the process of correcting

for — or 'equalising' — tonal changes caused by losses in the long telephone

lines, but today the term is more generally used to cover all types of audio

'tone' controls. To put it very plainly, an

equaliser is a frequency–selective filter that's able to cut or boost the level

of specified parts of the audio spectrum.

As you know, EQ is an immensely powerful mixing tool. It can be used to correct problems with the recording or to add character and tone where needed. For example:

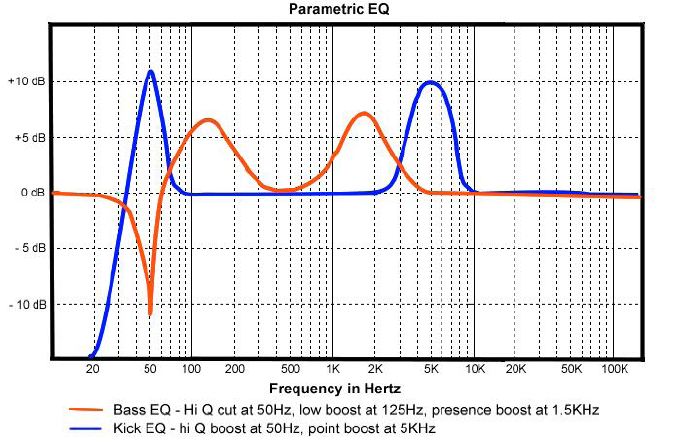

Are the instruments 'masking' one another? You can use EQ to carve out space for certain instruments to ‘sit’ together coherently, aka complimentary equalisation. The typical example is the kick drum and the bass guitar. Often, these two mix elements will be competing for space in your mix at around 50-130Hz. You can tackle this (and other similar clashes) by attenuating the bass guitar EQ at, say, 50-80Hz while boosting the kick drum slightly at the same point. At the same time, notch the kick and boost the bass guitar at 100-125Hz. This should allow the elements to work together and retain some power and presence in the final mix without muddying up the low end.

EQ can also be used to clean up the high and low end of a recording. Unwanted hiss or bass rumble can easily be removed with low pass and high pass filters respectively.

Conversely, sweetening EQ can be used to boost certain frequencies with the goal of adding colour, character and making your sounds more 'musical'.

How to EQ

When starting the EQ process, it can be

useful to be aware of some characterising EQ frequencies that can act as a starting-point.

The table below, published in Sound on Sound,

shows a useful EQ ‘cookbook’ to help

you with this:

Vocals

Most

voices have little below 100Hz so use low cut to remove unwanted bass

frequencies.

- Boxy at

200 to 400 Hz.

- Nasal at

800Hz to 1.5kHz.

- Penetrating

at 2 to 4 kHz.

- Airy at

7 to 12 kHz.

Electric Guitar

Cut

below 80Hz to reduce unnecessary bassy cabinet boom.

- Muddy at

150 to 300 Hz.

- Biting

at 800Hz to 3kHz.

- Fizzy at

5 to 10 kHz.

Bass Guitar

- Deep

bass at 50 to 100 Hz.

- Character

at 200 to 400 Hz.

- Hard at

1 to 2 kHz.

- Rattly/fret

noise at 2 to 7 kHz.

Acoustic Guitar

- Boomy at

80 to 150 Hz.

- Boxy at

150 to 300 Hz.

- Hard at

800Hz to 1.5kHz.

- Presence

at 2.5 to 4 kHz.

- Bright/scratchy

at 4 to 8 kHz.

- Airy

above 8 kHz.

Drums

- Kick

drum weight at 70 to 100 Hz.

- Kick

drum click at 3 to 5 kHz.

- Boomy

below 120Hz.

- Boxy at

150 to 300 Hz.

- Snare

definition 1 to 3 kHz.

- Stick

impact at 2 to 4.5 kHz.

- Cymbal

sizzle at 5 to 12 kHz.

You may also consider printing a 'cheat-sheet', like this to help you:

How do I find the nice/not nice frequencies?

Once you are in the ‘ballpark’, maybe by using the table or cheat-sheet above, you can start to think about boosting or cutting frequencies. A good way to approach this is by using a parametric EQ, with the Q set to say 1 and the boost turned up to max. You can then sweep through the frequency range to find nice, or not so nice frequencies, fairly quickly. Once you have homed in on the offending or pleasing frequencies, play with the amount of boost, cut and Q to arrive at the ‘best’ results for your track – this is a subjective process so experiment and find out what works for you. You should also strive to EQ ‘in context’ as much as possible. This means listen to the EQ changes over the whole mix rather than by soloing the track… or at least using a combination of these two methods. Remember, what sounds like an improvement to a solo’d individual track might sound terrible when combined with competing elements from the rest of the mix.

EQ Types and Jargon

There are a wide variety of EQs available to you

as a mixing engineer, from parametric, to static, to surgical (or corrective),

shelves, bandpass etc. etc.

This guide by Waves gives a useful overview.

5 Random EQ Tips

- It is important to remember that using EQ is another subjective skill. Keep this in the back of your mind as you mix and remember the famous Duke Ellington quote ‘If it sounds good, it IS good’.

Bass EQ – If you have mic and DI’d bass guitar tracks. Try hi passing the mic track for high end definition and character, then low pass the DI track for low end clarity and punch. Combine the 2 for a great bass tone.

Hi pass guitars. Guitars can fill up your mix very quickly. In my experience, some form of hi pass EQ is often needed on guitar tracks unless your mix is extremely sparse.

300Hz mud – From experience, I have found that it’s often useful to apply a cut at around 300-350Hz on a range of instruments (other than bass). Play around with the amount and the Q to achieve best results.

Next...

In my next post, I'll be looking at compression. As always, feel free to comment, question and suggest using the comment section below.

Take care,

Ian

Comments

Post a Comment